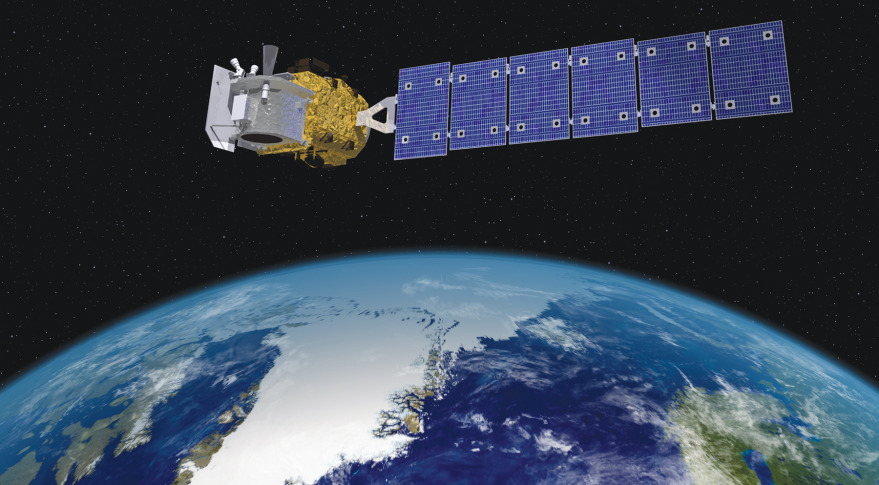

I’ve been following NASA’s ICESat-2 mission with great interest. Why? Maybe because I like words that start with three capital letters. Maybe because it’s going to make the best, most precise measurements of how the Earth’s ice sheets are changing, that anyone has ever made. Maybe for no reason at all.

ICESat-2 launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base a couple of weeks ago, into a near-polar orbit that will fly almost, but not quite, over the North and South poles every 90 minutes for the next 3-7 years. It’s carrying one instrument, which is a laser altimeter—a powerful laser that sends out ultra-short pulses of light, then measures how long they take to bounce off the Earth and come back. Using some mind-boggling optics, ICESat-2 will be able to measure the height of the Earth’s surface using only 12 photons out of the trillions it sends out from each pulse. This sounds crazy, but because it does this ten thousand times every second, it will be able to put together very accurate measurements of the height of the surface. On a clear day, ICESat-2’s measurements will be precise to something like the width of a cucumber (that’s a 40-meter long cucumber, because it needs to combine lots of measurements to be that precise. If you find one of those, send us a picture). The plan for the mission is to have ICESat-2 make these measurements on the same paths across the ice sheets over and over again, so that when glaciers get thinner or thicker, ICESat-2 will measure those changes.

Glaciers in almost every part of the world are getting smaller, often at jaw-dropping rates. That seems like a pretty clear sign that the world is warming, right? It’s good enough for most people, but at long last, there is paper to tell you exactly what ‘good’ and ‘enough’ mean.

Let’s back up for a minute. A glacier is a big piece of ice that slowly flows downhill. If it collects more snow in the winter than it loses to melt in the summer, it gets thicker, and, eventually, grows longer, and if the opposite happens, it thins and shrinks. Because it takes years for glaciers to grow or shrink, their changes tell us not so much about the weather this year or last year, as about how the climate has changed over the last few decades. What’s more, glaciers are big and easy to measure, so even in places where we don’t have great long-term records about weather, we often know how the glaciers have changed for centuries.